5 Tips for Learning a New Script

Perhaps you have a little spare time coming up, and you’d like to use it to learn a new calligraphy script?

A little aside on the terminology: in calligraphy, instead of saying font, we say script. This is because fonts are only used in typography. Scripts are something you write out.

And a script is “the” model for a style of lettering – each of us will produce our own hand – with our personal variations in what we create.

Marc Drogin gives a great definition of script and hand in his Medieval Calligraphy book:

“The distinction between a script and a hand should be understood. Within each script styles as many variations are possible as there are scribes to set them down. As one paleographer put it, “a script is the model which the scribe has in his mind’s eye when he writes, whereas a hand is what he actually puts down on the page.” Each scribe has his own hand, determined by training, skill, what he is writing, and his taste in embellishment. No manuscript is a perfect example of a script, but history does offer us thousands of examples of scribes’ hands. If we gather together the examples of many hands that appear to have been written within the same overall letter design, we can presume to identify a script.”

So here’s 5 tips for learning a new script.

1. Gathering resources

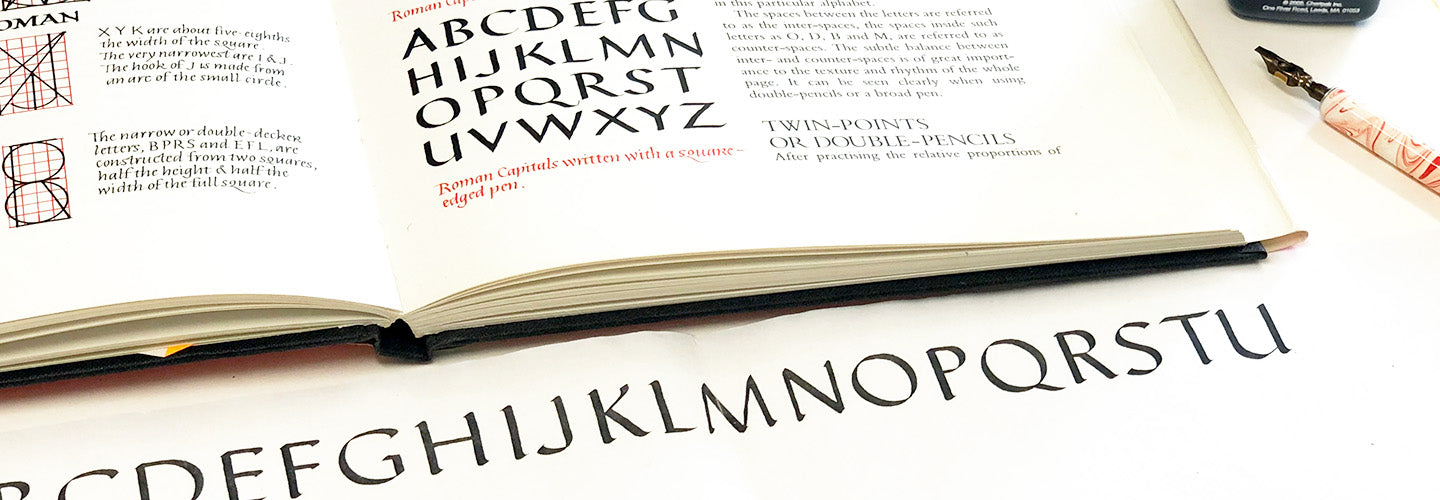

Gather together a few examples of the script. Unless you’re learning something really unusual you should be able to find examples in books and by using the internet. It’s very helpful to have a good historical example – because that’s where we should start in understanding how the scribe created the letters.

(If you’re a purist you might want to work out from the historical examples exactly what tools were used, how they were held, and how each letter was formed. Luckily for most of us, that wisdom has been imparted in excellent calligraphy books that explain everything from how far apart to rule your lines, through to the order in which the strokes of the letter should be made.)

Remember that a script is likely to have been in use for hundreds of years across perhaps a huge geographical area, so we should not be surprised to find that not all historical examples are the same.

Indeed the advice (for example on pen angle) may vary from one calligraphy book to another – this certainly doesn’t mean one book is wrong, simply that the author was using a different historical source to write their book, or may have simplified a complex set of rules so that a beginner doesn’t feel daunted.

Also we’ll find that the skill level of the scribes varied – just because it’s a historical manuscript it doesn’t necessarily mean that the lettering is excellent.

Fortunately there is advice available for great examples of most scripts (Stan Knight’s Historical Scripts book is a very helpful resource).

It can be helpful to make photocopies (enlarged if you can) of the best examples, so you can have a really good look.

2. Get started.

It’s usually best to practice the letters in their families (so you’re seeing how the repeating shapes help) – a good calligraphy instruction book should help with this, or you can start to stop the repeating shapes as you write.

Sometimes starting in pencil can be good, as it builds your confidence. Letters are not going to look like the historical example until you’re using a similar tool though (such as a broad edged pen).

Don’t be afraid to trace the shapes, or to add pencil lines to follow, and refer back to the historical examples often.

3. Keep going.

Work big. Yes – it means your errors will show – but that’s the point!

It’s easy to get stuck on one or two letters as you learn the new shapes (in Foundational the G tends to cause furrowed brows!)

The repeating and repeating of the same letter is not (in my opinion) the right approach here.

The Rule of 5 says that once you’ve written the same letter 5 times further repetitions are likely to be worse rather than better.

(Why is this? Because your frustration increases, and the number of things you spot that you don’t like about the letter increase too.)

So don’t write out lines and lines of the same letter.

4. Putting it together

Your aim should be to be writing real words and sentences. That, after all, is why letters exist.

A sheet of paper, properly ruled up, with generous margins, puts you in the right frame of mind for making good letters.

Find some words to write that are interesting.

If a letter goes wrong, instead of crossing it out just make a note to yourself in the margin.

Be specific in your criticism – again write it in the margins. (‘it’s rubbish” is no help).

Try and find positives too (it helps to pretend that the sheet was written by someone else – you’ll be kinder then!)

Hang one of your practice sheets on the wall where you’ll see it as you pass. It changes your perspective on what has worked and what has not. Often it’s easier to judge the spacing of letters and words when the sheet is hanging on the wall.

Seek the views of others – calligraphers or not, both views are helpful.

5. Use it!

Don’t wait until you think your lettering is perfect – USE it! Edward Johnston was a keen advocate of the creation of “real things” as the best way to develop your lettering.